Jessica Tsai, above, lounges in her lab before its March opening at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles

By: Trish Adkins

One of Jessica Tsai’s research projects produced hundreds (and hundreds) of gigabytes of data. If you printed this information out, you would need at least 10,000 cases of printer paper, which is pretty unimaginable, so Tsai likes to use the very technical measurement of “a lot.”

But don’t let her casual measurement methodology fool you. Tsai, a pediatric neuro-oncologist and Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation-funded researcher, is serious about data. She lists data sets like a grocery list — ticking off transcriptomic, genomic, and epigenetic, the way you would list eggs, milk, and bread. She’s exhilarated when noting things like reproducible results, data deposits and standards. She’ll rattle off her expectations for data sharing in her lab that opened in March — organized lab notebooks, standardized coding, and raw data storage — without taking a breath.

When you ask Tsai about her time outside the lab with patients, she doesn’t hesitate. But her voice changes, shaking a little as she recalls, quietly, the times she had to deliver the news to parents that their child’s brain tumor is rare, research or data are lacking, no standard treatment is known to work, and the prognosis is poor.

“As I say that out loud as a clinician, my scientist brain asks what the heck? I can’t believe I am saying this,” said Tsai, who received an ALSF Young Investigator Grant in 2020 while she was a postdoc at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston and is now opening her own lab at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles.

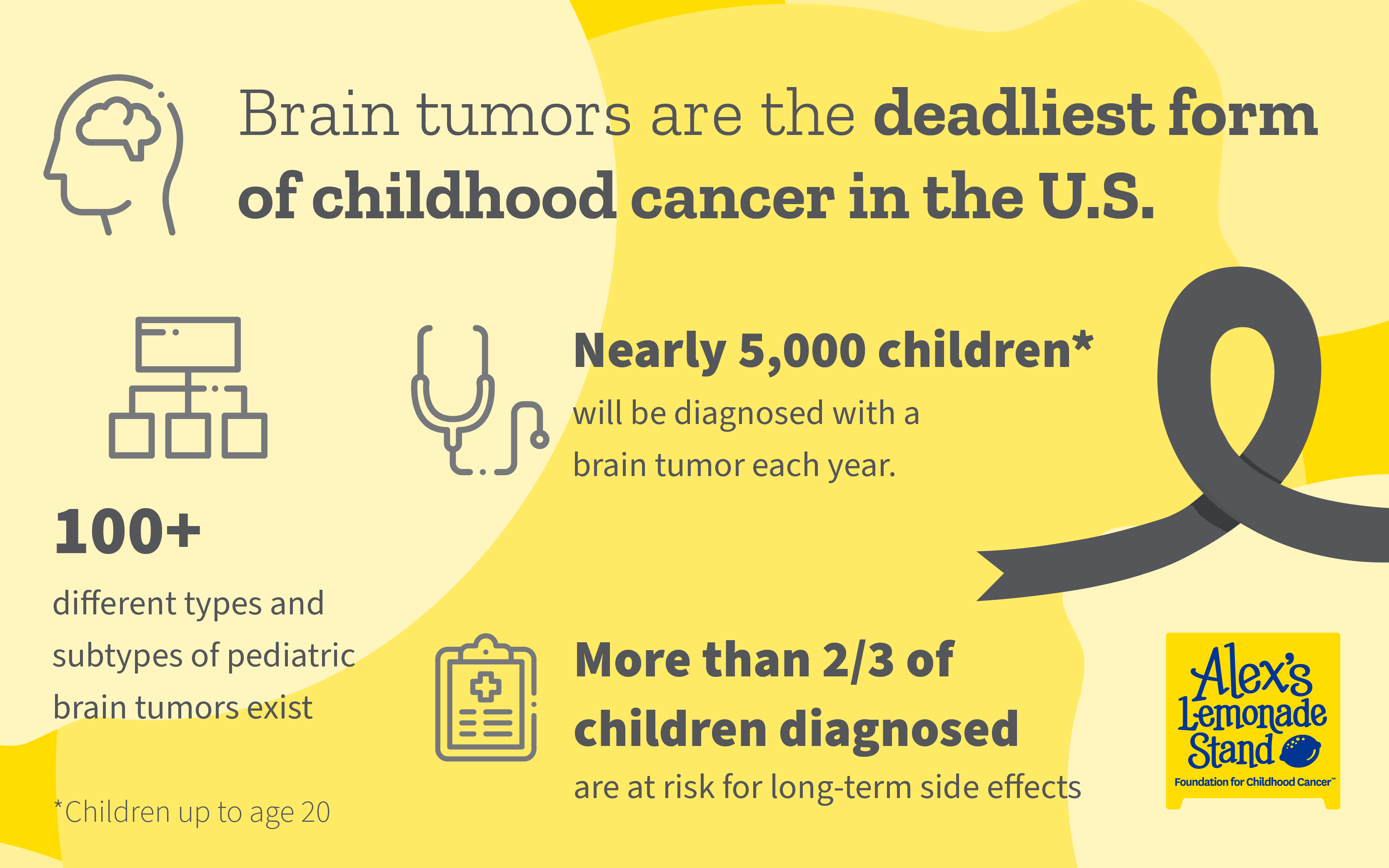

She sees children with some of the deadliest tumors, including diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG). DIPG tumors mix with healthy tissue in the brain, sort of like salt and pepper, making them inoperable, unstoppable, and deadly; only 10% of children live more than two years after diagnosis.

“We just haven’t made enough progress,” said Tsai.

***

In her lab, Tsai will focus on researching the mechanisms that make brain tumors grow and figuring out ways to stop them. Her research approach aligns with the trends in cancer studies — focusing on the genetic characteristics of brain tumors, as well as the epigenetic changes that happen in tumors. Epigenetics studies how cells in tumors turn genes “on” and “off” to drive growth and treatment resistance. These changes don’t change the DNA of cells; but they do change how that DNA is understood by the body. Tumor environment — i.e. the body and brain that hosts the tumor — can influence epigenetic changes. This type of research requires genetic sequencing, which provides researchers with important information about cancer cells. This data is processed, replicated, validated, and used in a variety of experiments, producing even more information. The data growth is unstoppable in how it expands, sort of like bread left to rise and rise, spilling over the confines of the mixing bowl.

“It’s totally never ending,” said Tsai, who combats the vastness of the data with a dedication to organization and backing up all data in at least three separate locations. “I’ve heard stories of researchers going to publish and all their data is gone,” she said.

Tsai recently attended a workshop led by ALSF’s Childhood Cancer Data Lab that walked her through principles in data organization and sharing. Taught by the lab’s team of data scientists, it focused heavily on reproducible research practices. Being able to produce the same results from an experiment, again and again, is critical to proving validity. If you can do something once, that could be meaningful, but if you repeat something successfully, well, then you might be onto something. The Data Lab offers these free trainings several times a year to childhood cancer researchers. After the training, the collaboration does not stop. Tsai said she often turns to the Data Lab’s Slack channel with questions.

While Tsai says there are not universally clear guidelines on data management (referring to the atmosphere as a “bit of the Wild West”), she is setting clear guidelines for her lab, inspired by the Childhood Cancer Data Lab training, to ensure efficiency and collaboration internally and externally. “I feel like this is especially important for us as pediatric oncologists,” said Tsai.

Marissa Coppola, who worked with Tsai at Dana-Farber and moved 3,000 miles from Boston to Los Angeles to join the lab as a technician, says that Tsai’s excitement over discovery is infectious — she is often shouting from her desk that everyone must come see the data she is collecting. Coppola says that Tsai also has exceptionally high standards for work, but she also makes sure everyone is equipped to work at that high level, especially when it comes to data.

Tsai describes the challenge of pediatric cancer research as being one of scarcity and abundance. Pediatric cancer is uncommon, as compared to adult cancer, so tissue samples and cell lines can be hard to come by, especially for the rarest cancer types. And there is that issue of abundant data, which if not coded, deposited, and harmonized correctly, can lead to a duplication in efforts, something that Tsai says research doesn’t need. Collaboration is essential and her perspective is that all childhood cancer findings belong to the greater research community and should be shared. “It’s actually all our data,” said Tsai.

Tsai has already made major contributions in the study of DIPG. Using her Young Investigator Grant, Tsai led a team researching FOXR2, a mutated gene that drives the development of DIPG. That grant resulted in a 2022 Cancer Research paper detailing the prevalence of FOXR2 across human cancer types.

The study also gave Tsai a firsthand look at how data sharing can power even more research. Her team analyzed 10,000 tumor samples and found that 8% contained FOXR2. In the journal article, Tsai included her analysis, as well as links to the raw data.

“Two different people reached out to us about the data set,” said Tsai. “I think it’s cool that they were able to go into the data set and find something useful for them and that data has now served multiple purposes.”

***

Growing up, Tsai didn’t even know being a pediatric oncologist was a possibility. She recounted her abandoned aspirations: astronaut, WNBA star and marine biologist. While at Stanford University, she describes checking out a neuroscience lab and finding herself intrigued by the brain — and having fun with neurons and synapses. “I thought, this is perfect. I’m going to study this. I’m going to study Alzheimer’s,” said Tsai.

Then she did her neurology rotation and, at first, hated it. It wasn’t until her rotations took her to pediatrics that she knew she found her thing. Through a fortuitous introduction to a pediatric oncologist, she decided she could combine neuroscience and her love of pediatrics to take care of kids with brain tumors.

Working with kids in the clinic allows Tsai to see the holes and gaps in research and care very clearly. She often reminds her lab technicians studying tissue samples that those tumors are not just cells, they are someone’s family. “This is a person, connecting to a whole family and all these people who care about them are connected to them,” said Tsai.

Tsai is connected to her patients as well and invested in their success — thriving and surviving. In February before she made the cross-country trip with her husband and dog, Tsai said goodbye to patients still in treatment — looking ahead to her time at CHLA and making an impact for more kids.

“You know there’s the potential for there to be eighty, a hundred years of life ahead, and if we don’t find better treatments and cures you just lost all of that, right? You lose the potential for them to go to college. You lose the potential for them to meet their spouse or to have kids or whatever impact they were going to have on the world,” said Tsai. “We simply have to do better.”

May is Brain Tumor Awareness month. You can learn more about pediatric brain tumors and the pressing need for more research, here (and you can share the facts on social media!) Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation founder Alex Scott believed that if we all work together, we would find cures for childhood cancer. In that spirit, you can sign up to be part of our monthly giving program, the One Cup at a Time Club! Learn more here.